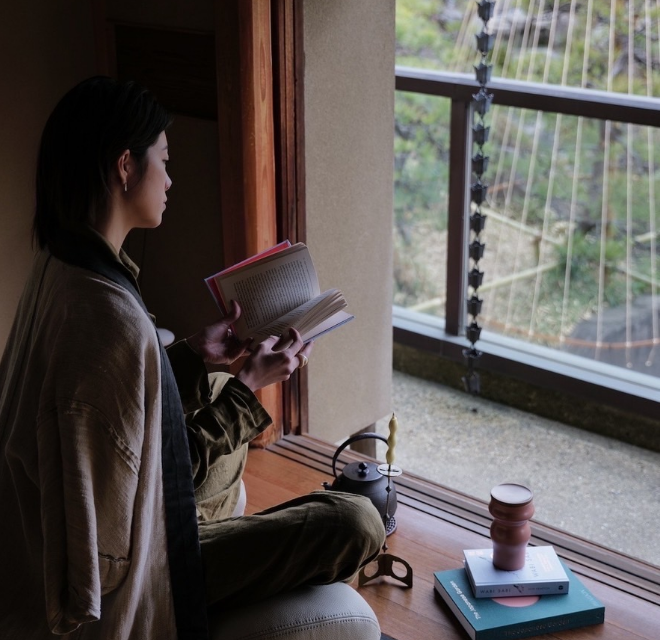

In search of the natural beauty found in traditional culture unique to Japan, Azumino City in Nagano Prefecture has plenty. We headed to Tensan Center to learn about wild silkworms that produce a beautiful green silk that exude a sense of new growth and life.

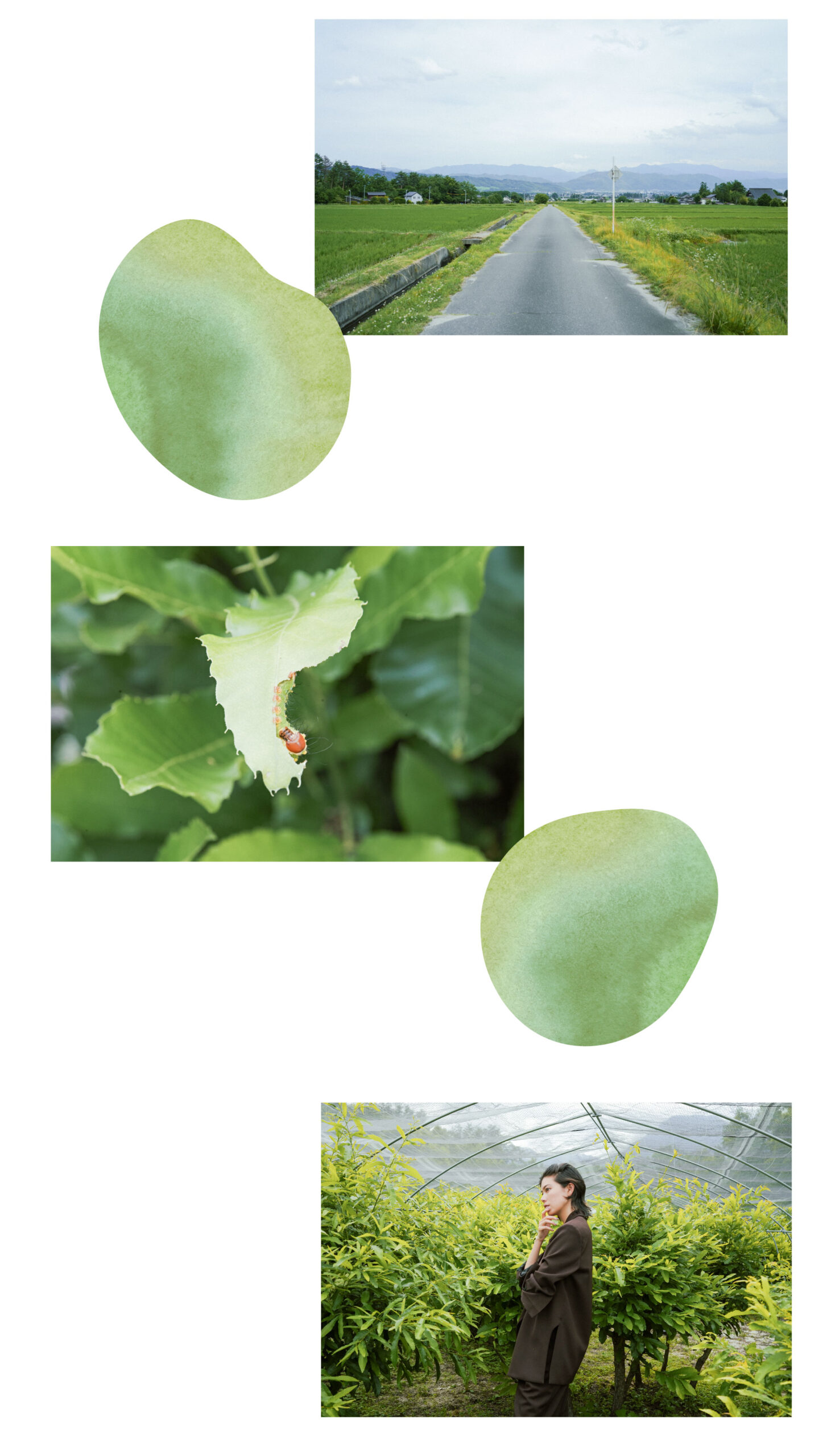

The silk is produced by carefully unwinding the cocoons excreted by the silkworms is generally categorized as white or unbleached silk, but the wild silkworms that are native to Azumino produce a glossy green thread instead. The wild silkworms feed on plants like sawtooth oak, and in comparison to domesticated silkworms (specifically bred silkworms), their cocoon length is 1.3cm or longer and weigh 4g and above. These cocoons are referred to as mako or yamamai.

The birthplace of wild silkworms, which have been protected to this day without being tampered with as a natural native species, is the Hotaka Ariake district in Azumino City. It is said that wild eggs were collected since around 1781 and the breeding began. The sawtooth oak fields at the foot of the Northern Alps are relatively dry and infertile with little rain. These fields have developed into one of Japan’s leading silkworm production sites as the ideal farm for wild silkworms. During the Edo period (around 1848-1853), the collection of raw silk from these cocoons began and with the coinciding development of foot-operated looms led to mass production. As a result, the Hotaka area was prospering, producing a peak of 8 million cocoons around 1897. However, due to disease, the eruption of Mount Yakedake, and war, production of these wild silkworms ceased. Efforts to re-establish the practice didn’t resurface until 1973, when the local government of Hotaka at the time actively collaborated with local farmers to revive the culture centered on wild silkworm breeding.

Historically speaking, silk was at the epicenter of global culture and trade as a product of high value. Silk from domestic silkworms’ white cocoons originated in China. At the end of the Edo period, Japan was rapidly absorbing foreign cultures at the time when the country was opening up to the rest of the world. Silk was sold at a high price, and Japan was on the economic decline at that time. The shogunate’s solution was to issue a recommendation for sericulture in order to enrich the country by promoting the silk trade. The breeding of domestic silkworms soon became common practice all across Japan, and various breed improvements were made to raise silkworms that were easier to handle and were able to produce longer and stronger threads. The Tomioka Silk Mill in Gunma prefecture is one such fruit of those labors, as it was formally recognized as a World Heritage Site in 2014 as the largest mechanical silk mill in Japan that was established all the way back then.

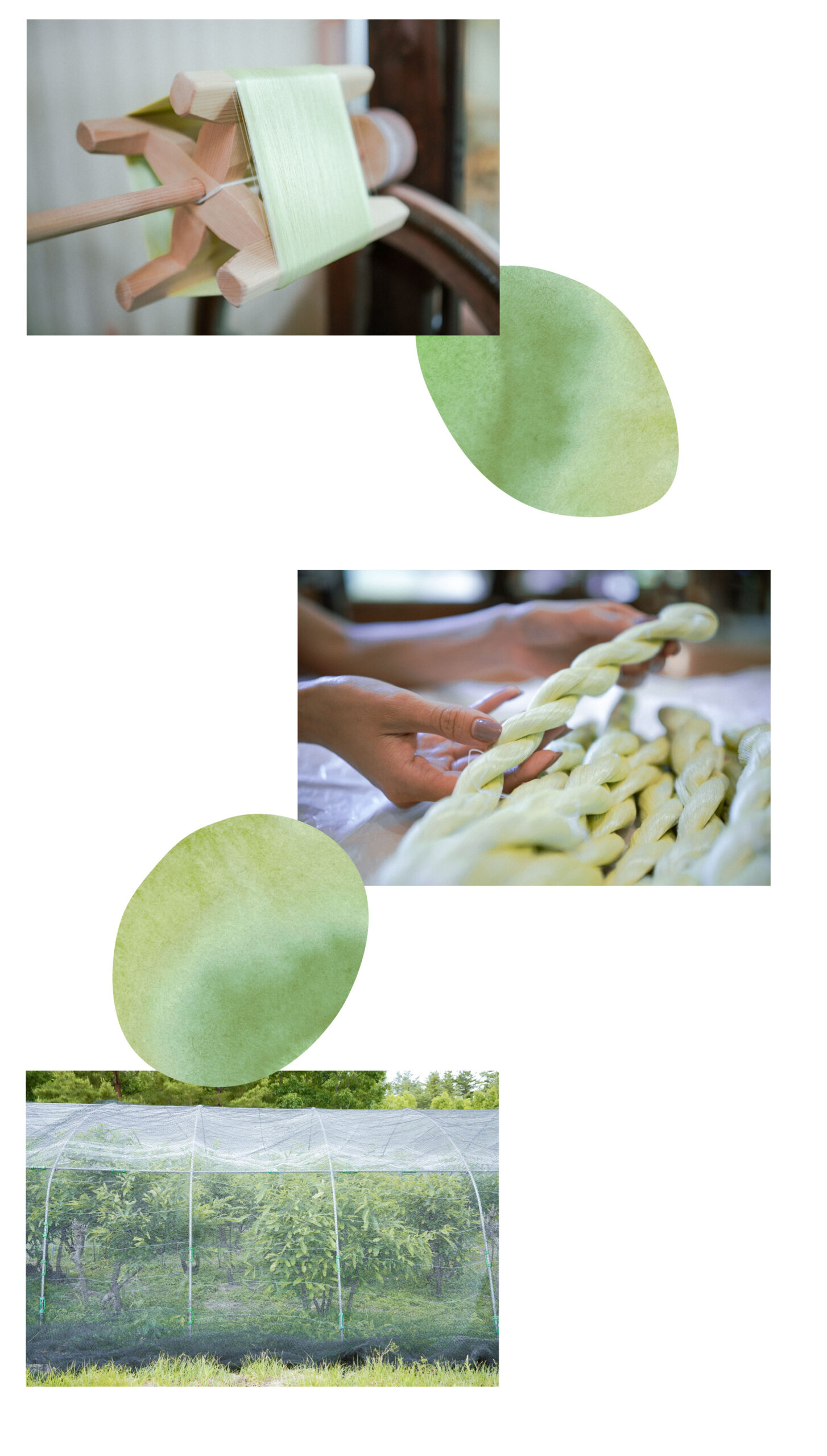

The appeal of silk produced specifically by the wild silkworms is the retention of their natural luster in the threads, and their rarity. The luster is so brilliant, the thread has the nickname “fiber diamond”, and only 700m of thread can be harvested from one cocoon. In comparison to domestic silkworms, which can produce up to 1,500m of raw silk, wild silkworms yield less than half the amount. The raw silk from seven cocoons are hand-spun into a single thread, and those singular threads are put through a loom to make a kimono. As wild silk thread is elastic (the domestic variety is not), it takes a high level of skill to create rolls that do not twist. Currently there are only a handful of artists left who have inherited this skill of weaving wild raw silk. As the manufacturing process is painstaking, kimono made from wild silk is highly coveted.

Wild silk is also used to produce Shinshu Tsumugi (pongee), a traditional craft textile from Nagano prefecture. Shinshu Tsumugi is made by loosening the cotton-like fibers of the silkworm cocoon before the threads are extracted from the cocoons. Because Shinshu Tsumugi is made with wild raw silk, the resulting texture from the natural dyeing process thereafter is unique. The resulting fabric is also known for its lightness and durability. In the early Edo period when wild silkworms were plentiful, many lengths of the pongee produced was exported to Kyoto. This textile has ancient roots, believed to originate from Ashiginu, a similar cloth woven from silk dating back to the Nara period (710-794). Despite the labor and time required to produce this textile, the preservation of the craft is a testament to its inherent cultural value.

Tensan is still in practice at Tensan Center and nearby farms. The wild silkworm eggs are harvested via traditional methods and are carefully transferred to breeding forests with a view of lush surroundings in spring, where the silkworms hatch and grow together with new shoots. After molting four times, the cocoons are ready for harvest to be turned into fiber diamonds.

The preservation of this weaving culture that has remained unchanged for centuries is our way of returning to our Japanese roots. To pay due respects to nature’s gifts, the artists who keep this highly technical craft alive, to be grateful for life by not letting these things fade away into history and instead listen and learn from what they can teach us. Moving forward, we are eager to see how future lifestyles can be shaped by the harmonious push and pulls caused by technology, nature, and cultural factors.

Photography: Arata Funayama

Edit & Text: Yuka Sone Sato

Design: Mammy Horie

Translation: Kelly Yeunh